By gracefully yielding to gravity, you can meet challenging poses with efficiency and ease.

At the heart of all yoga philosophy lies the premise that suffering arises from a mistaken perception that we are separate. Whether we feel separate from other human beings, or separate from the trees we walk under, the rocks we walk upon, or the creatures that walk, fly, swim, and crawl around us, yoga insists that this separation is an illusion. The life force is intrinsic to all things, and any separation we feel from anything is a separation from that ever-renewing source of sustenance. Almost all of us have felt the veil of this false notion lift at some time in our lives and experienced the feeling of goodness and wholesomeness that comes when we feel ourselves to be a part of everything. And most of us have found that this feeling of wellness and happiness rarely arrives through pushing and pulling and molding ourselves into who we think we ought to be. Instead, this feeling of oneness, of being happy for no particular reason, seems to arise when we simply accept the moment and ourselves just as we are. As Swami Venkatesananda tells us in his translation of the second verse of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, “Yoga happens . . . .” Of course, Venkatesananda goes on to name the conditions in which yoga occurs, but I think “happens” is the key word in his translation. It implies that the state we call yoga can’t be forced.

I don’t mean to say that if you sit on your backside, watching TV and eating Cheetos, yoga will happen to you (although it’s possible). Any authentic spiritual path requires a great deal of work, commitment, tenacity. But along with making the necessary effort, we simply have to give ourselves over to what I like to call the Larger Mover and let ourselves be moved. The fact is we have always been moved by this larger force. We may resist, we may hold on for dear life, we may go kicking and screaming, but eventually we get moved whether we like it or not. Not only is it easier to go quietly, it’s in our best interests to do so—because however our lives are changing in any moment is reality, and reality (no matter how bad or good it seems at the time) is always the path of least suffering.

Let’s make this philosophical discussion concrete by anchoring it in the body. Each of us organizes our sense of separateness not only through our thoughts and ideas but also through our body and its relationship to gravity. We have many choices in this relationship, but all of them fall on a continuum between utter collapse into the Earth and rigid, propped-up pushing away from it. In this column we will look at how we can develop a more intimate and connected physical relationship with the ground underneath us and the sky above us, and how we can use this relationship as a powerful tool to undermine our false notions of separation.

Collapse, Prop, or Yield

In a “collapse” relationship with gravity, the body lacks tone and sags downward into the Earth. Our breath feels like stagnant water, dull and lacking in vitality, and we may be depressed and lethargic. We often try to remedy this state of collapse by swinging to the “prop” end of the spectrum, constantly pushing the ground away, projecting ourselves into space by holding the body in a state of hypertonicity, and negating our connection to the Earth. Our breathing becomes strident, high up in the chest, and tense. We feel distrustful, convinced that the only way we’ll stay vertical is through constant, self-willed effort.

The third choice, balanced between these two extremes, is to yield to gravity. When we yield our body weight—when we trust the Earth to support us—an upward rebounding action effortlessly lifts us away from the Earth. Our muscles come into a balanced tone, neither too gripped nor too released, and our breath centers itself in the middle of the body. Gravity becomes our friend, not our foe, and we feel in harmony with ourselves. We make the necessary effort, provide the necessary work to maintain the body’s integrity, and then we let something beyond what we know and control happen to us. We trust that life will support us.

Tadasana: Exploring Your Relationship with Gravity

Take a moment to feel these three relationships to the ground. Stand with your feet hip-width apart in Tadasana, and allow your body to collapse downward in a posture of submission or dejection. This stance is how many of us started our yoga practice. Notice your breathing in this state of collapse. Can you fill your lungs, or do they feel hemmed in and compressed?

Once you’re familiar with this state of collapse, shift to the state of propping. Engage what I call the push and push pattern: Push down hard through your feet, and keep on pushing. Gather all your muscles, and drive your spine and head upward. Now notice how your breathing has changed. Has it become shallow and moved high up into your chest?

Next, let’s explore the possibility of neither giving up nor struggling, but of gracefully yielding. Instead of pushing the Earth away, slowly release the hardness in your abdomen and allow the weight of your lower body to pour down into the Earth. Imagine your weight streaming down through your legs like sand in an hourglass. As you give your weight to the ground, the soles of your feet will immediately soften and broaden, and your breathing will spontaneously deepen and relax.

Once you truly give your weight to the Earth, something magical happens. As you yield to gravity, the release rebounds upward in an effortless flow that moves into your torso, lengthening your spine and head toward the sky.

If you don’t feel this rebounding flow of force, you may be yielding too much and returning to a state of collapse. Try starting again from a strongly propped position and then slowly allow yourself to release your weight into the Earth. Gauge the level of muscle tone you must use to maintain the integrity of your skeletal structure and prevent your bones from collapsing into the spaces of the joints. In active yielding your body becomes a clear conduit for both downward and upward moving forces.

Give half of yourself to the Earth and the other half to the sky. Experiment with shifting your torso forward and back until you find the place where your belly, chest, and head best catch this rebounding flow of force.

Keep shifting between the three relationships with gravity—collapse, prop, and yield—until you can easily identify them. Spend some time familiarizing yourself with how each relationship feels—not only the physical sensations, but also the emotions each relationship evokes.

In my explorations, I’ve discovered certain physical and emotional patterns specific to each of these relationships with gravity.

For example, I agree with Body-Mind Centering teacher Lynne Uretsky when she says, “Whenever the relationship of yielding to the Earth is lost, breathing is restricted.” In addition, whenever I don’t allow the ground to support me, I find that my center tightens and I can’t feel a strong, integrating connection with my limbs or with my sense of self. On a more subtle level, I find that each of the three relationships with gravity has a different effect on the circulation of fluids in my body—synovial and cerebrospinal fluids, blood and lymph, the fluids surrounding my organs, and so on. When I collapse, my fluid circulation decreases and becomes sluggish; when I prop and push, it feels static and frozen. Yielding seems to create the optimal conditions for fluid circulation. When I’m in the yielding state, I feel all these fluids moving through my body in a pumping action that is intimately connected to the rhythm of my breath. You might like to go back through the exploration in Tadasana again and see if you can feel a difference in the movement of fluids in your body as you shift from collapse to prop to yield.

Virabhadrasana II: Balancing Effort and Ease

Many of us find that Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose II) demands a lot of effort, tempting us to shift from the balanced state of yielding into either collapsing or propping and pushing. Even if you feel you already do this posture well, consciously using it to explore your relationship with gravity can help you clarify where you need to focus more energy and where you’re working harder than necessary.

Begin by standing with your feet wide apart and parallel. To find exactly the right distance between your feet, turn your left foot in slightly, turn your right foot out 90 degrees, and bend your right knee until your thigh parallels the floor (or comes as close to this position as is comfortable for you). Your right knee should be exactly above your right ankle, with your shin perpendicular to the floor. If your right knee extends beyond the ankle, you need to widen your stance; if your knee is behind your ankle, you need to narrow your stance.

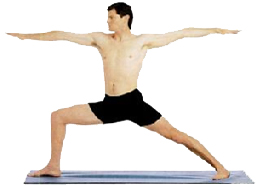

Once you’ve determined the proper distance between your feet, make sure you’ve allowed the left side of your pelvis to swing slightly forward (Figure 1). For less flexible people the left hip will come well forward, for more flexible people the left hip will be further back, but no matter how flexible you are it is not anatomically possible for the left hip to be flush with the right hip unless you compromise the healthy alignment of your joints. If you try to force the left hip back, your right thigh will rotate inwards, placing strain on your right knee, and your left sacroiliac and hip joints will be compressed (Figure 2).

Allow the left side of your pelvis to swing slightly forward. This action lets you align the middle of your left instep, your right sitting bone, and your right heel, protecting your leg and pelvis joints.

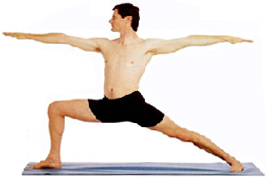

In this photo the model is jamming the left side of the pelvis back in an attempt to keep it flush with the right. As you can see, the right sitting bone is now behind the line between the right heel and left instep, putting stress on the right knee and compressing the hip and sacroiliac joints.

Now that you’ve safely positioned your hips, let’s ensure you aren’t over-torquing your right ankle or knee. Look down and draw an imaginary line from the heel of your right foot to the arch of your left foot, and make sure that your right sitting bone is directly above this line. Once you establish this connection, yield the weight of your front foot into the ground, and send the rebounding flow of energy horizontally back through your front leg. If you’re properly aligned, you’ll feel the force travel up the leg, through the pelvis, and all the way into the back leg and foot. Maintain a strong diagonal line from your thigh through your knee, shin, and foot; if you collapse in your knee or ankle, you will stress and perhaps harm those joints.

Now that you’ve correctly aligned the foundation of the pose, let’s see what happens when you collapse. Allow your torso to deflate and lean over the front leg. Your abdomen will become heavy, decreasing the space in your hip sockets, and your back knee will drop toward the ground (Figure 3). Feel yourself being overwhelmed by gravity. Don’t stay long, for most assuredly this is not a good way to practice: Collapsing places tremendous, potentially injurious pressure on your joints and ligaments.

When you allow your body to release too completely into the earth, you place unhealthy pressure on your joints, and force can’t flow efficiently through your body. Notice how the model’s pelvis weighs heavily on his femurs, and how the bend at the knee undermines the strong support of the back leg.

Bend your front knee again, while continuing to extend through your back leg. Instead of collapsing, begin to push down through your feet, and maintain a constant push away from the Earth for as long as you stay in the pose (Figure 4). Notice what happens as you hold the pose by pushing the Earth away: Your muscles work relentlessly, your breath tightens, and fluid circulation decreases throughout your rigid tissues.

When your prop your body off the Earth by constantly forcefully pushing down with the feet, the natural upward lift of the body becomes effortful and strained. Notice the tension in the model’s hips, chest and arms.

Now, before you get too tired, try yielding. Exhale deeply and allow the weight of your lower body to flow into the ground. Without collapsing, give yourself to the Earth and let it hold you up (Figure 5).

Yielding to gravity without collapsing or propping generates a natural rebound that moves lightly and effortlessly up through the body. The body balances, grounding into the Earth and expanding into the sky.

After a moment of yielding, you’ll feel a rebounding force travel back through your legs, into your pelvis, up your spine, and through your head. Let this force move through you.

As you remain in the asana, notice how yield and rebound alternate in a rhythm intimately related to your breath. You cannot breathe fully unless you yield, and you cannot yield unless your breathing is open. Let yourself be curious and explore how breath, yield, and rebound interact: Where in your breath cycle do you feel the rebounding force most strongly? There is no right or wrong answer to this question; your personal, ongoing process of inquiry and discovery is what makes this practice yoga.

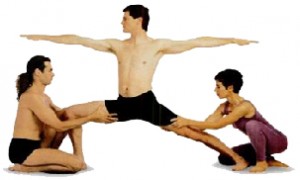

If you are having difficulty feeling the “yield” relationship to gravity in Virabhadrasana II, get help from a couple of trustworthy yoga friends. Have one person place her hands firmly around your back thigh while the other person holds underneath the front thigh close to the hip joint (Figure 6).

You can help a friend feel the anchoring action of the legs by strongly drawing the thigh bones out of the pelvis on the exhalation and allowing the femurs to retract slightly back on the inhalation. Make sure you hold the thigh close to the hip joint and synchronize you action with your friend’s breath.

As you breathe out, have your friends give strong traction to the thigh bones. Make sure their pull directly follows the line of the bones—the diagonal of the back leg toward the back foot, and the horizontal line of the front femur towards the knee.

As you inhale, sense into your lower body. If you are listening and allowing the natural movement to happen, you’ll feel your legs actually retract slightly back into your body as a result of the pulse rebounding up from the Earth. Ask your partners to follow this rhythm. As you inhale, they draw strongly out on your thighs; as you exhale, they maintain firm contact with your legs but allow the thighs to retract back toward your pelvis. If you get confused, go back to the pattern of “push and push.” Then, on an exhalation, release the tension in your muscles and again listen for the rebounding flow of energy coming back from the Earth.

When you’re ready, try Virabhadrasana II to the left. On this side, continue to explore the three relationships to gravity. How much can you yield before it turns into collapse? How much can you support the rebound before it becomes a rigid propping? Coordinate your exploration with your breath. As you breathe in, think of yourself as a glassblower, breathing life into the form of the asana from the inside out. As you breathe out, release from the center of your abdomen, allowing the release to travel along both legs and into the ground.

The Power of Yielding

As you explore, you’ll become more and more familiar with the physical and emotional characteristics of each pattern. In the pattern of “push and push” or “prop,” muscles tend to grip the bones, creating hardness in your tissues. This pattern impedes your circulation. When you’re pushing too hard you’ll tire quickly and waste products will build up in your muscles, making them feel heavy and sore the next day. In addition, whenever you hold yourself apart from your breath and the Earth, you create a frozen, isolated, defensive state of mind.

In the pattern of “collapse,” muscles hang from the bones, joints lack integrity, and force is unable to travel through you efficiently. Your bones become like misaligned railroad tracks: When a train of force moves through you, it moves from side to side or completely off the track, rather than in a powerful, unbroken line.

By contrast, when you yield in your relationship with gravity, force can transfer smoothly from bone to bone, and your muscles can work with maximum efficiency. You may notice that when you let the Earth hold you up, you can stay in the pose a great deal longer than you can when you’re pushing the Earth away. With some practice, you can feel all the muscles in your body moving with your breath in an undulatory rhythm.

In Virabhadrasana II, your leg bones will actually migrate away from and back toward your pelvis, becoming a part of the breathing process. In fact, when we get out of our own way, no part of the body is held separate from the breath. When you allow yourself to be moved by the breath as it rebounds from the Earth, your mind becomes open and receptive, returning to its naturally inquisitive nature. But all of this will only happen if you let it happen: You cannot achieve yielding through effort. It can only happen when you begin to let go of effort, balancing intention with release.

My own discovery of the power of yielding came through illness. Some time ago I was chronically ill for more than a year, and during this time I became terribly thin, losing much of my muscle bulk and strength. Previously I had been given to effort-ful and highly controlled practice, but after my illness I no longer had the physical capability to hold myself up in my old way.

After many months of practicing nothing but restorative postures, one day I tentatively stepped onto the mat to do a standing pose. Trembling with the effort and astounded at my weakness, I paused for a moment and stood very still. Taking a deep breath, I asked if there was something else that could hold me up. And then, as I exhaled, the Earth answered.

Benefits:

• Develops strong legs and arms.

• Increases overall strength and stamina.

• Releases the hip joints and stabilizes the knee.

• Tones the entire body.

• Works indirectly to balance the spine.

This material was originally published in : Yoga Journal Jan-Feb 1999